Regulations around lot size and land use are driving up the cost of new homes across Wisconsin, according to builders and economists who say some of the problem is fixable—if cities are willing to act

“A lot of us would not be able to afford the houses we’re living in now if we were buying now,” said Middleton Common Council member Lisa Janairo.

A 2021 study by the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) found that 23.8% of the cost of a new single-family home—about $95,000 on a $400,000 home—can be attributed directly to regulation. These costs include permitting fees, mandated design changes, and requirements like large setbacks and uniform mailboxes, according to the Badger Institute.

RELATED: Locked In for 400 Years: How Evers’ Veto Will Hurt Wisconsin Homeowners

“I was hoping it would make people a little more cautious before adding more,” said Paul Emrath, the study’s author and an economist trained at UW-Milwaukee. He emphasized that not all regulations are bad, but many go too far.

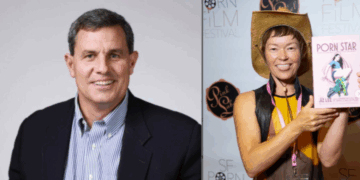

In Washington County, County Executive Josh Schoemann estimated the regulatory burden per house falls somewhere between $60,000 and $90,000. “We’re not talking about nickels and dimes here,” he said. “But dollars and ten-dollar bills.”

Builders Say It’s Not the Land—It’s the Rules

Steve DeCleene, president of Pewaukee-based Neumann Companies, said unnecessary mandates on materials like trucked-in stone for sewer backfill can add $10,000 per lot. He says cheaper and equally effective alternatives—like reusing dirt and posting a bond for repairs—are often ignored.

“The incentives get perverse,” said DeCleene, noting that cities don’t bear the cost of the materials they require. “Unless a city is relentlessly focused on keeping costs down, requirements pile up.”

DeCleene compares two 80-acre projects: one in Dodge County near Beaver Dam, the other in Waukesha County. The Dodge County site produced 171 lots—2.14 houses per acre—versus just 97 lots, or 1.21 homes per acre, in Waukesha. Though the land in Beaver Dam is cheaper, lot size and regulatory differences accounted for over $90,000 of the per-lot cost savings.

“Lot size, which gets down to zoning, is the biggest factor,” DeCleene said.

Why Some Cities Are Making It Work

Beaver Dam is one city trying to address the issue. Economic Development Director Trent Campbell said the city partnered with DeCleene’s firm to allow smaller lot sizes and streamline approvals. The result: new homes under $400,000—a rarity in today’s market.

“Our employers are telling us that one of the critical factors in finding employees is housing,” Campbell said. “They have to find a place to live at a reasonable cost.”

RELATED: Millions Spent, Little Tracked: Wisconsin DEI Audits Reveal Oversight Failures

In Middleton, Janairo said smaller lots at the Redtail Ridge subdivision—some just a tenth of an acre—were met with surprising acceptance. “People are much more accepting of single-family homes than of apartments,” she noted.

The Resistance to Change

Not all municipalities are on board. Muskego Mayor Rick Petfalski pushed back against DeCleene’s example, saying his residents value open space over dense development. “Many people move to our community because of our great schools and safe community, but also because of the rural county feel,” he said. “They enjoy seeing rolling countryside and farms.”

Petfalski said developers are chasing profits, not public interest, and warned against any state mandate on lot sizes.

But DeCleene argues that resistance to more affordable housing comes from a vocal minority. “When you talk to people in a community, they want housing that’s more grand than their house,” he said. “You know who doesn’t come out? The 100 people who are going to buy my homes.”

The Bigger Picture

While DeCleene says he avoids trying to “persuade” cities to change, he sees the broader stakes: “It’s the American dream to own a home, and it’s at risk.”

If current zoning trends continue, he warns, fewer people will be able to buy homes—especially younger families and first-time buyers. “We’re becoming a nation of renters,” he said.

Janairo echoed the concern: homes priced in the $400,000s might not be “affordable,” but at least they’re “attainable”—for now.